I want to finish with a quick look at the main ways that pattern was used in this piece, and how this affected the rhythm of the piece. The primary pattern motif used was a simple swirl.  The swirl forms the spirals of the garden’s raked gravel and is seen again in the swirls of the clouds. To add variation to the rhythm of the clouds the spiral was changed slightly on each long side. One side has four swirls per pattern and they are facing down, while the other side has three swirls per pattern and they are facing up. The three-swirl pattern also has less swoop to its swirl. This variation is possible because the pattern is divisible. It is the repetition of the swirl that creates movement and really brings the clouds to life.

The swirl forms the spirals of the garden’s raked gravel and is seen again in the swirls of the clouds. To add variation to the rhythm of the clouds the spiral was changed slightly on each long side. One side has four swirls per pattern and they are facing down, while the other side has three swirls per pattern and they are facing up. The three-swirl pattern also has less swoop to its swirl. This variation is possible because the pattern is divisible. It is the repetition of the swirl that creates movement and really brings the clouds to life.

The swirl used as the base pattern for the gravel is non-divisible because the entire set of swirls together is needed to create the pattern. Each swirl’s base line was adjusted to reflect the shape of its particular stone. The swirls are flipped in a pattern that demonstrates alternating rhythm in the garden’s main courtyard. This adds interest while keeping the focus on the stones in each spiral’s center.

gravel is non-divisible because the entire set of swirls together is needed to create the pattern. Each swirl’s base line was adjusted to reflect the shape of its particular stone. The swirls are flipped in a pattern that demonstrates alternating rhythm in the garden’s main courtyard. This adds interest while keeping the focus on the stones in each spiral’s center.

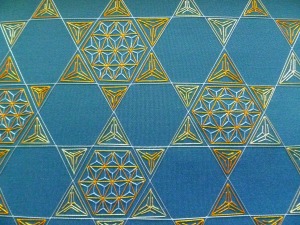

Pattern is also a part of the geometric design on the outside lid of the box and can help us think about how people are the same, yet different. One of the fascinating parts about the Chinese Geometrics technique is that all of the internal design is created by a single embroidery s titch – the Fly Stitch. By varying the length of the ‘arms’ of the stitch you can create a vast number of variations from a single concept.

titch – the Fly Stitch. By varying the length of the ‘arms’ of the stitch you can create a vast number of variations from a single concept.

I chose to limit the variations I used to keep the design from becoming chaotic, but if you examine the original inspiration for the outside lid you will be amazed at the number of variations from a single simple stitch. The piece’s interest is created by color as well as fly stitch variations. This helps us think about how much variety can come from simple tools and materials. Do not we all have basically the same bodies, yet each person is unique and beautiful.

As I have shared some of the design features of my Zen Garden box I have also shared some of my ideas and reflections on the lessons it makes visual. I invite you to share what you find as you reflect on the Zen of Life.